Teaching students to write is a perennial concern for homeschooling parents. We all know how crucial writing well is, both in academics and in daily life. Yet many children—not to mention adults—struggle when asked to put pen to paper (or fingers to keyboard).

Students need to be taught to write, and that instruction should be explicit. Composition practice should begin in kindergarten, with simple copywork, and should continue through the end of high school. Composition is a daily subject, like math; students need consistent instruction and practice to master the many skills involved.

Because students should be writing every day, they need plenty of topics to write about. Without explicit guidance, students often end up writing opinion pieces about personal interests. Those types of assignments have their place, of course, but let’s be honest: you don’t really want to read another ramble about Minecraft, do you? Instead, I suggest using the material your student is already learning in the major content areas as the “stuff” of their writing practice. We call this writing across the curriculum.

Exploring the World through Story provides plenty of writing practice in the literature content area. But what about history or science? If you’re using a formal curriculum, maybe even a textbook, it probably comes with comprehension or discussion questions. Many parents default to doing these orally—or skipping them altogether—but they make perfect writing topics, even for very young kids. Even if you aren’t using a textbook, it’s easy to create writing assignments from informational text.

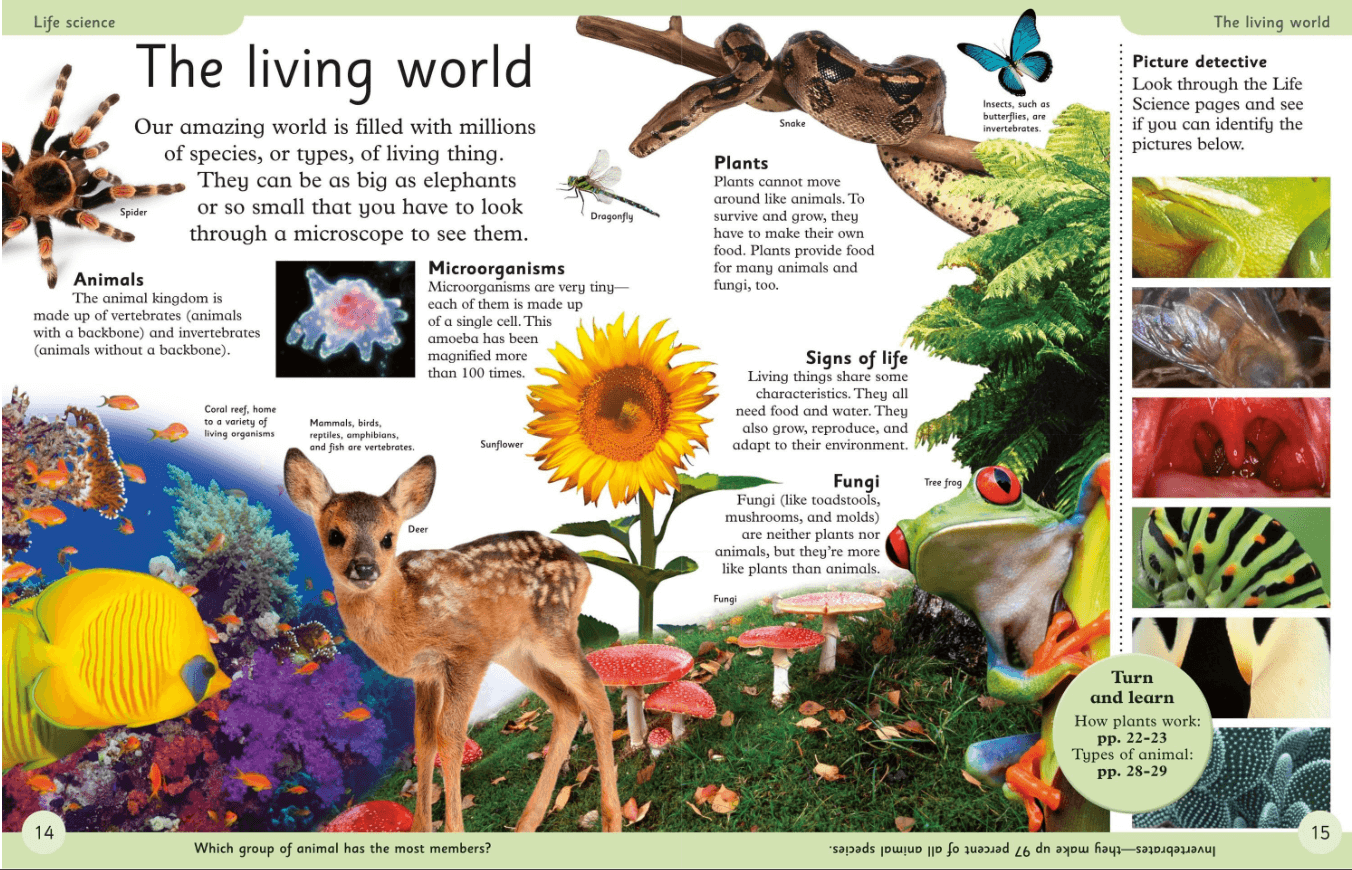

Let’s look at some examples. Here is a two-page spread from the DK First Animal Encyclopedia, which would be a read-aloud in K-1 or -2 and an independent read for grades 3-4.

Although this text does not include comprehension questions (there are trivia-style questions in the footer), you can easily create them yourself. For a child in the K-1 range, a question might be How are plants different from animals? The student provides an answer orally—possibly after having their attention directed to the information under the “Plants” heading—which the parent writes down. The student can then copy the sentence to practice handwriting and mechanics, while also reinforcing the content of the reading. Older students could write 2-3 sentences independently to answer the question:

Plants are different from animals. They cannot move around, and they have to make their own food. Plants can also be food for animals and fungi.

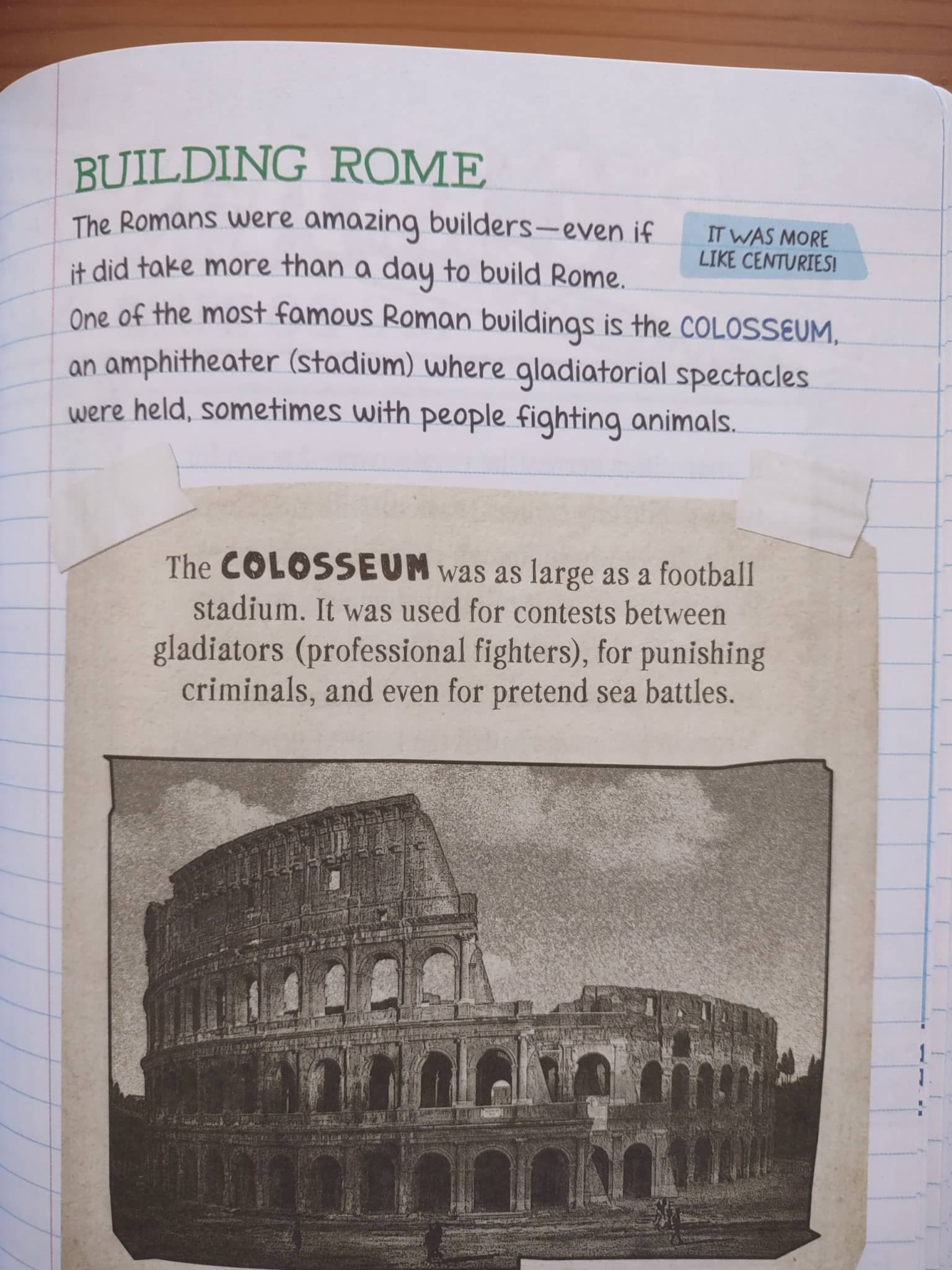

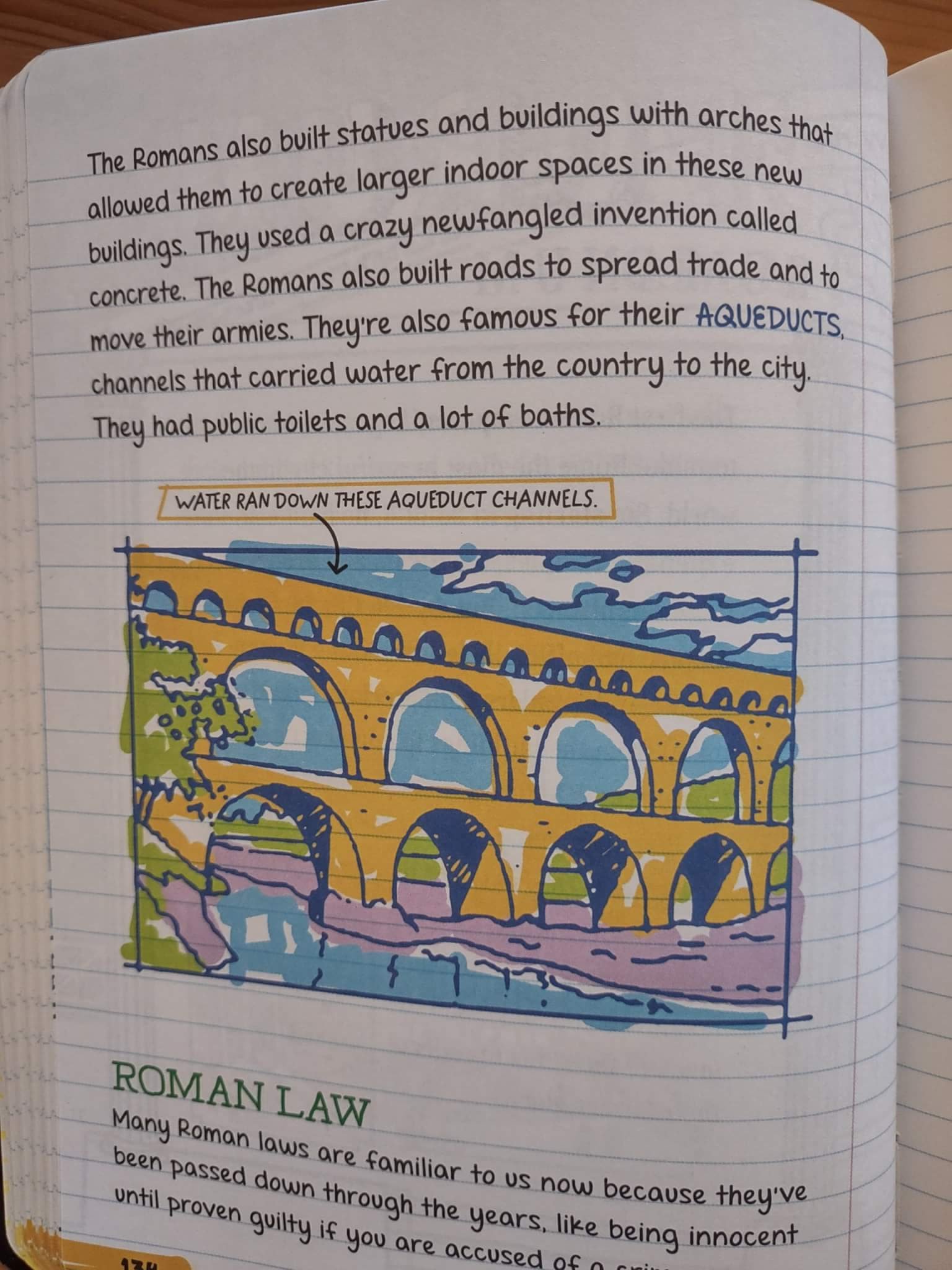

What about history? Here’s a middle school example from Everything You Need to Ace World History in One Big Fat Notebook. At this stage, students should be able to write an informational paragraph or short essay based on their reading. Since this text is a study guide, it includes questions (and sample answers):

If you’re feeling ambitious or the student needs extra support, you could create a graphic organizer to help the student structure their response, reminding them to use a topic sentence, supporting sentences, and a concluding sentence. Perhaps your student is familiar with the RACES paragraph format (taught in EWS) and could use that to answer the question. In any case, by assigning this question as a writing exercise, you help the student remember both the content of their reading and the structure of an informational paragraph.

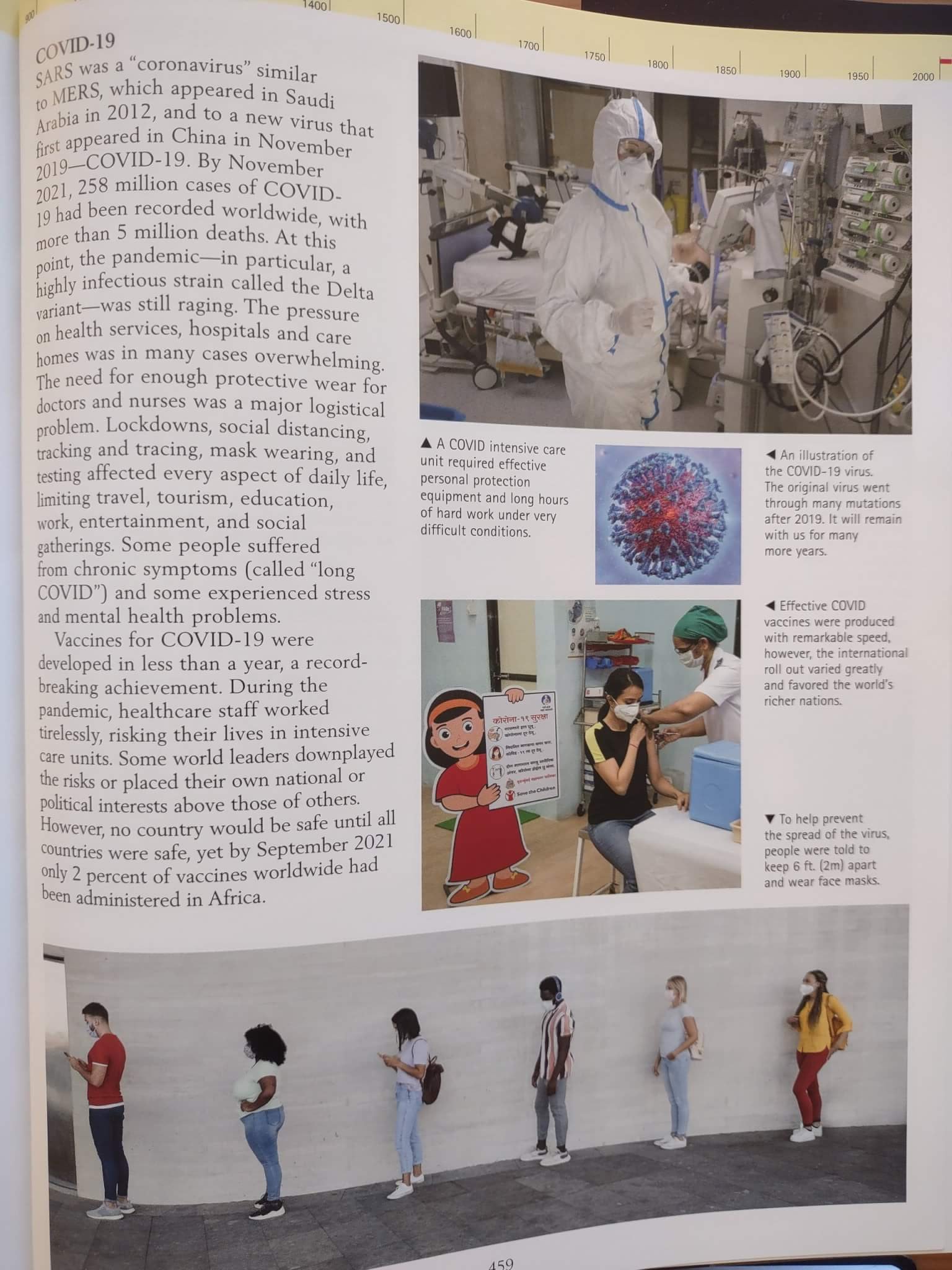

Here’s one last example, this one from the most recent edition of the Kingfisher History Encyclopedia, which you might use in middle or high school.

Again, no questions are provided here, so you will need to formulate one based on the reading. How about What challenges did society face due to the COVID-19 pandemic? Older students could either write a paragraph summarizing the information given in the reading, or (better yet) they could write a short essay focusing on one challenge and do further research on it. For example, they might choose to write about the effects of lockdown on the performing arts, highlighting both the challenges faced by artists and the innovative ways they responded to those challenges.

Writing across the curriculum benefits both students and teachers. Students must do more than simply pass their eyes over written text. If they know they are expected to write about a topic, they will be more likely to pay attention as they read, distinguish main ideas from supporting details, and master domain-specific vocabulary. As they write, they reinforce their existing knowledge of paragraph and essay structure, sentence variation, vocabulary, mechanics, and all the other elements of good writing. For teachers, such assignments act as on-the-spot assessments of student understanding. They also make excellent additions to weekly quizzes and unit exams (highly recommended for all students, including homeschoolers, since we know retrieval practice is vital to moving information into long-term memory). Finally, if you need to submit writing samples as a part of a homeschooling portfolio or for placement in an online school or other program, assignments like these demonstrate how well the student is able to handle academic writing. Writing across the curriculum checks all these boxes and more.

For more ideas on teaching writing across the curriculum, see The Writing Revolution, Write By Number, or Sprouts: A Gentle Writing System.

Copyright 2025 by Drew Campbell, Ph.D. All rights reserved.

Drew Campbell, Ph.D., has worked in education since the 1980s and holds degrees in German literature and language from Bennington College and Washington University in St. Louis. Dr. Campbell is the author of Living Memory, I Speak Latin, and Exploring the World through Story, and co-author of How to Homeschool the Kids You Have. A former homeschooling parent, classroom teacher, and school administrator, she now works as an independent curriculum developer at Stone Soup Press.